Uncovering Subtle Electric Signatures to Open New Frontiers in Space Science

All English text on this page has been translated automatically. Some sentences may be unnatural.

Many people start their day by checking the weather forecast and deciding what to wear or how to plan their schedule. Using a car navigation system or a map app on a smartphone has also become part of everyday life. Behind these convenient services are artificial satellites orbiting the Earth. They play an indispensable role not only in daily life but also in fields such as disaster prevention and national defense, making them one of the most critical technologies for national security.

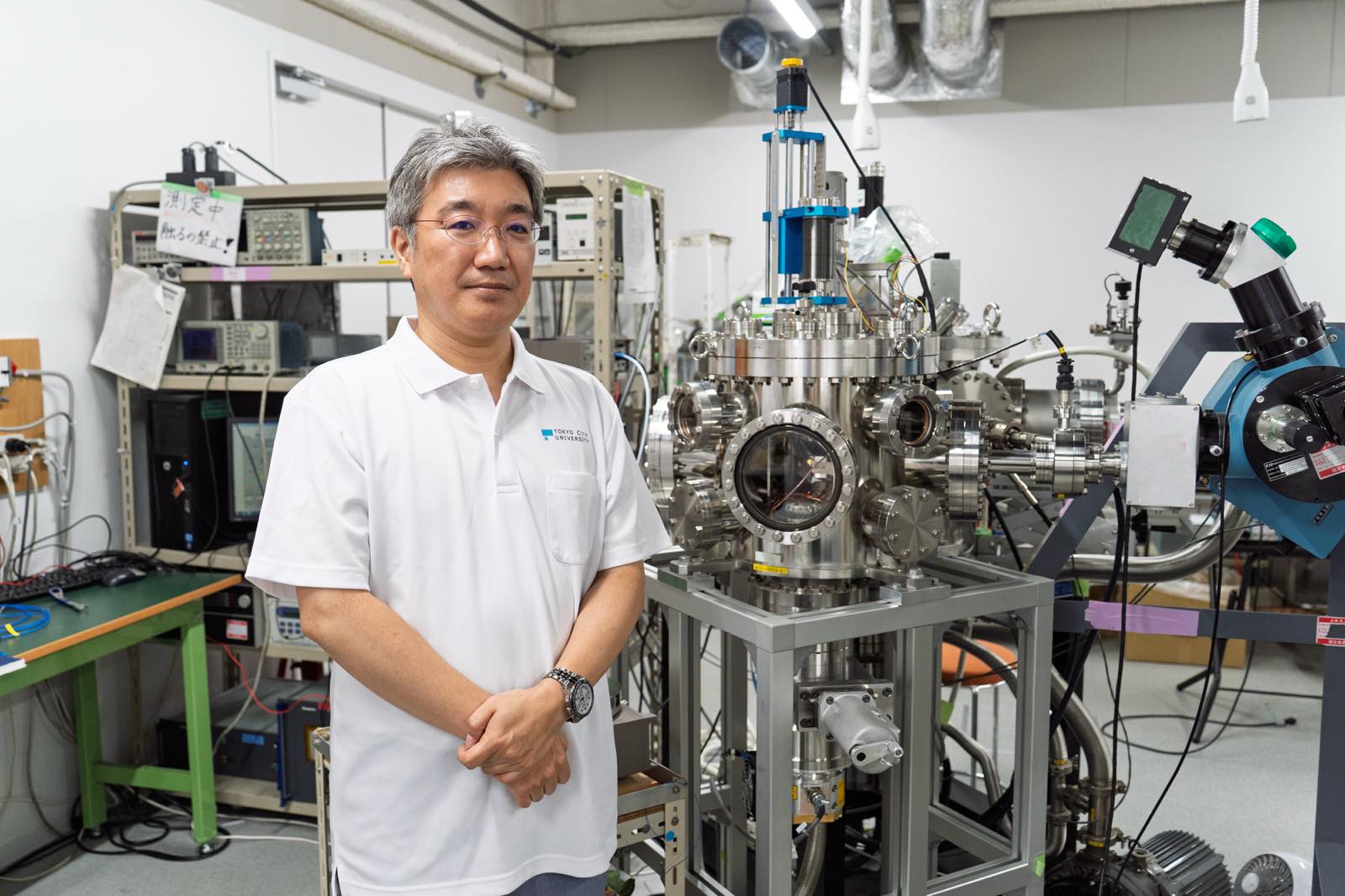

At the same time, the development and launch of satellites require enormous costs, and long-term stable operation is therefore essential. One of the causes of failures and accidents involving spacecraft such as artificial satellites and probes is a phenomenon known as “charging.” Professor MIYAKE Hiroaki, of the Faculty of Science and Engineering, is developing technologies to measure the charging behavior of materials used in spacecraft.

When we imagine an artificial satellite, we tend to picture a body covered with metal. In reality, however, very thin plastic films are used, serving to protect onboard equipment from heat. Outer space is an extremely harsh environment with drastic temperature fluctuations due to direct exposure to sunlight. In addition, satellite orbits are constantly exposed to radiation. Invisible electrons and protons travel at high speeds, and when they collide with these films, electric charge gradually accumulates, eventually leading to strong charging. Excessive charging can cause electrical discharge, which may result in serious accidents. It is also said that microscopic space debris can collide with a charged satellite and trigger a discharge.

“This is called electrostatic discharge. In winter, when we wear a sweater, static electricity builds up in our bodies, and when we touch metal, we sometimes feel a shock. A similar phenomenon occurs on artificial satellites in space. For humans, it is just a brief painful sensation, but for satellites, it is not so simple. Vital electronic equipment can fail and become unusable,” explains Professor MIYAKE.

It is said that more than half of satellite accidents are caused by electrostatic discharge. In fact, Japan’s Earth observation satellite “Midori-2,” launched in 2002, was forced to terminate its mission after about one year due to damage caused by charging and discharge. The protective film became strongly charged under radiation exposure and discharged between itself and the power lines. Cracks formed in the insulation of the power cable, creating a short circuit between the transmission and grounding lines, which prevented power from being supplied from the solar panels.

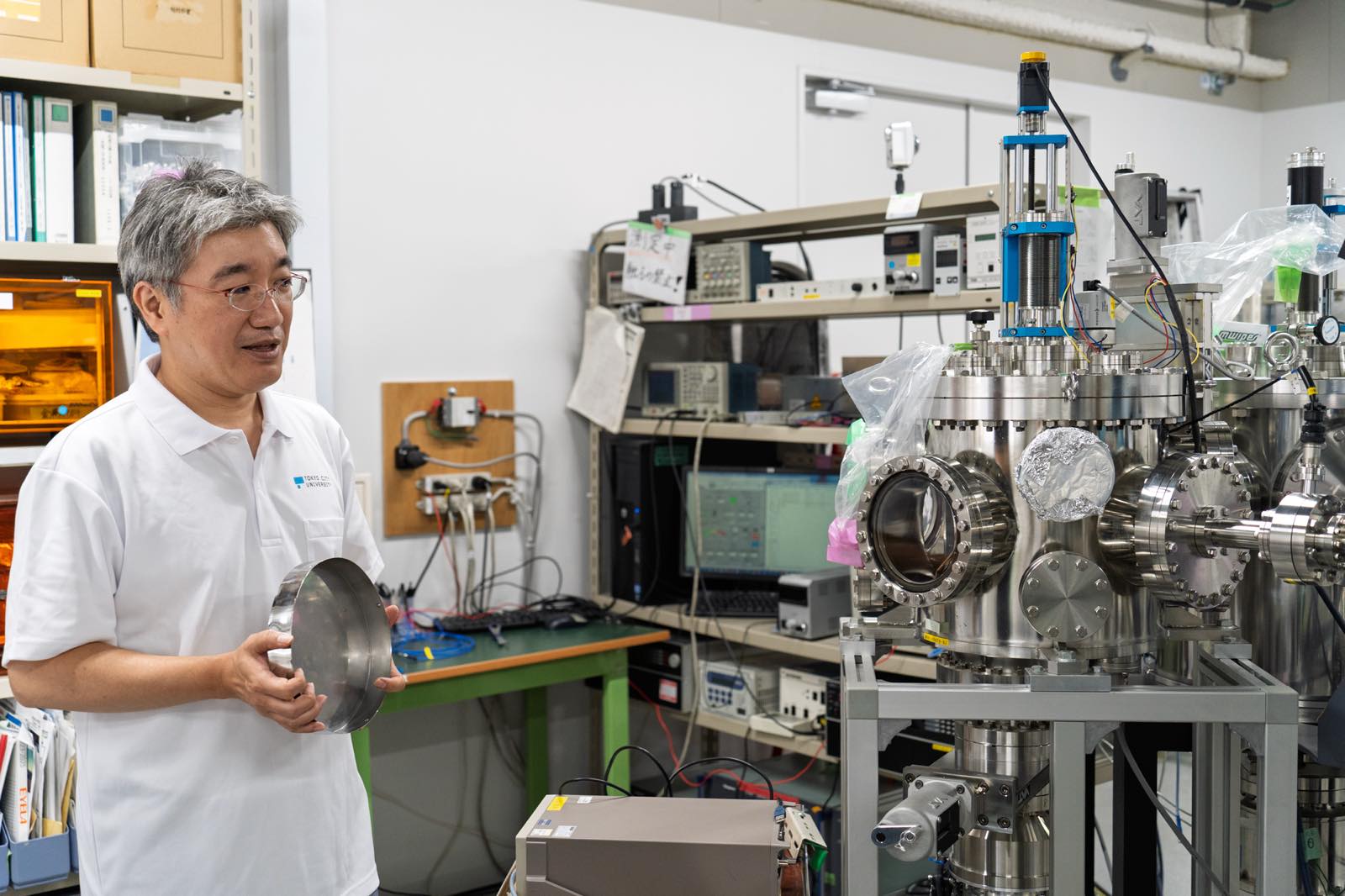

To improve satellite reliability, countermeasures against charging must be incorporated from the design stage. In Professor MIYAKE’s laboratory, the charging properties of materials used in satellites and space probes are analyzed on a daily basis.

“Depending on the objective, we develop our own measurement and evaluation systems for ground-based testing and analysis. The technology to measure charging was first developed by our laboratory. As a leading laboratory in this field, we feel a strong sense of responsibility. We are also actively conducting joint research with international organizations and companies,” says Professor MIYAKE.

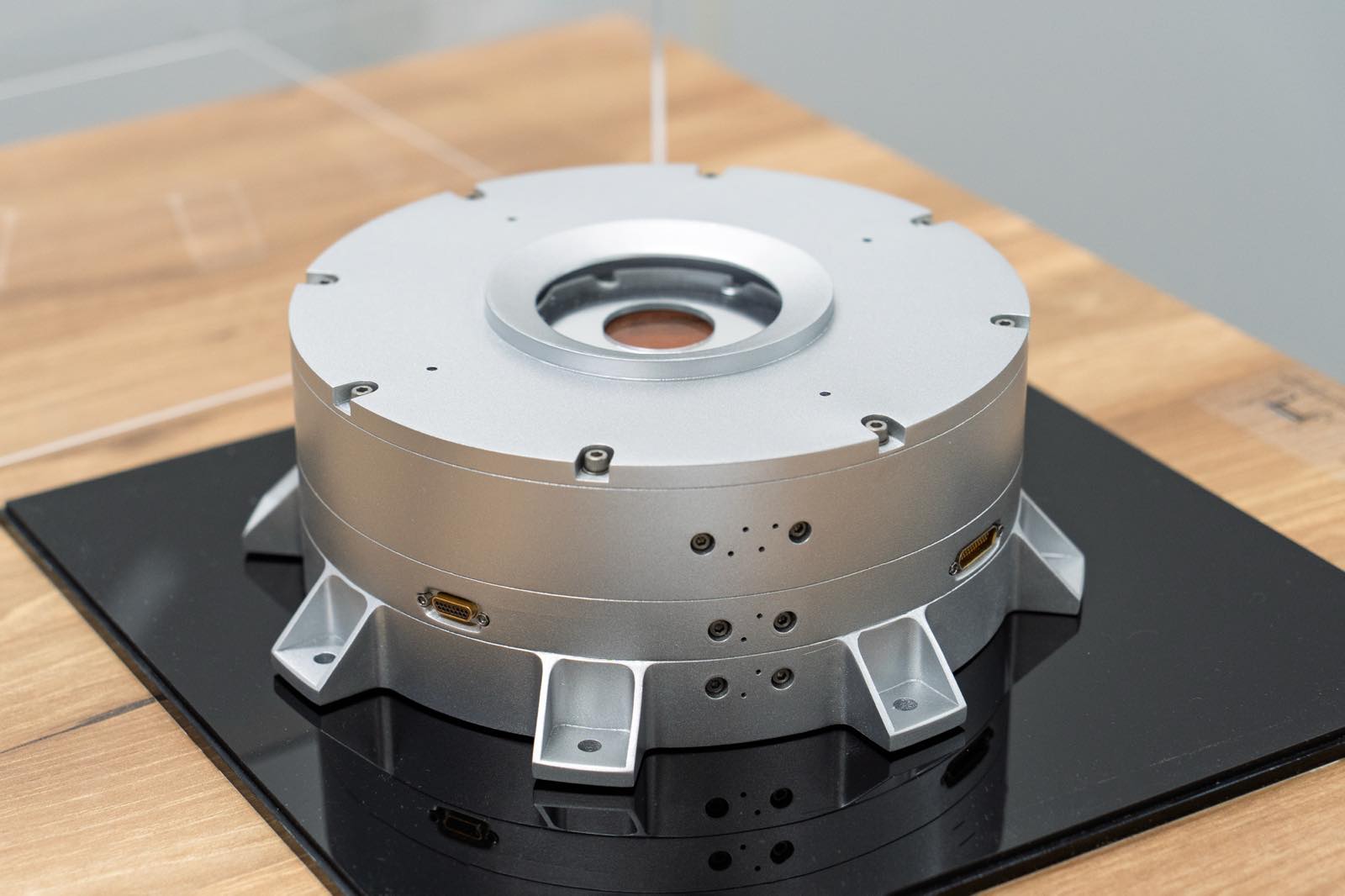

In addition to satellites, future spacecraft for lunar exploration and other missions may be exposed to unforeseen radiation effects, making even more advanced and robust countermeasures against charging necessary. Professor MIYAKE’s laboratory is also developing instruments that can be mounted on satellites to measure charging directly in the actual space environment.

“This instrument contains an onboard computer, so as long as it has a power supply, it can transmit data to the ground. To ensure it can withstand the space environment, we must repeatedly conduct tests and use radiation-resistant components. We are working hard to begin actual operation within the next few years,” notes Professor MIYAKE.

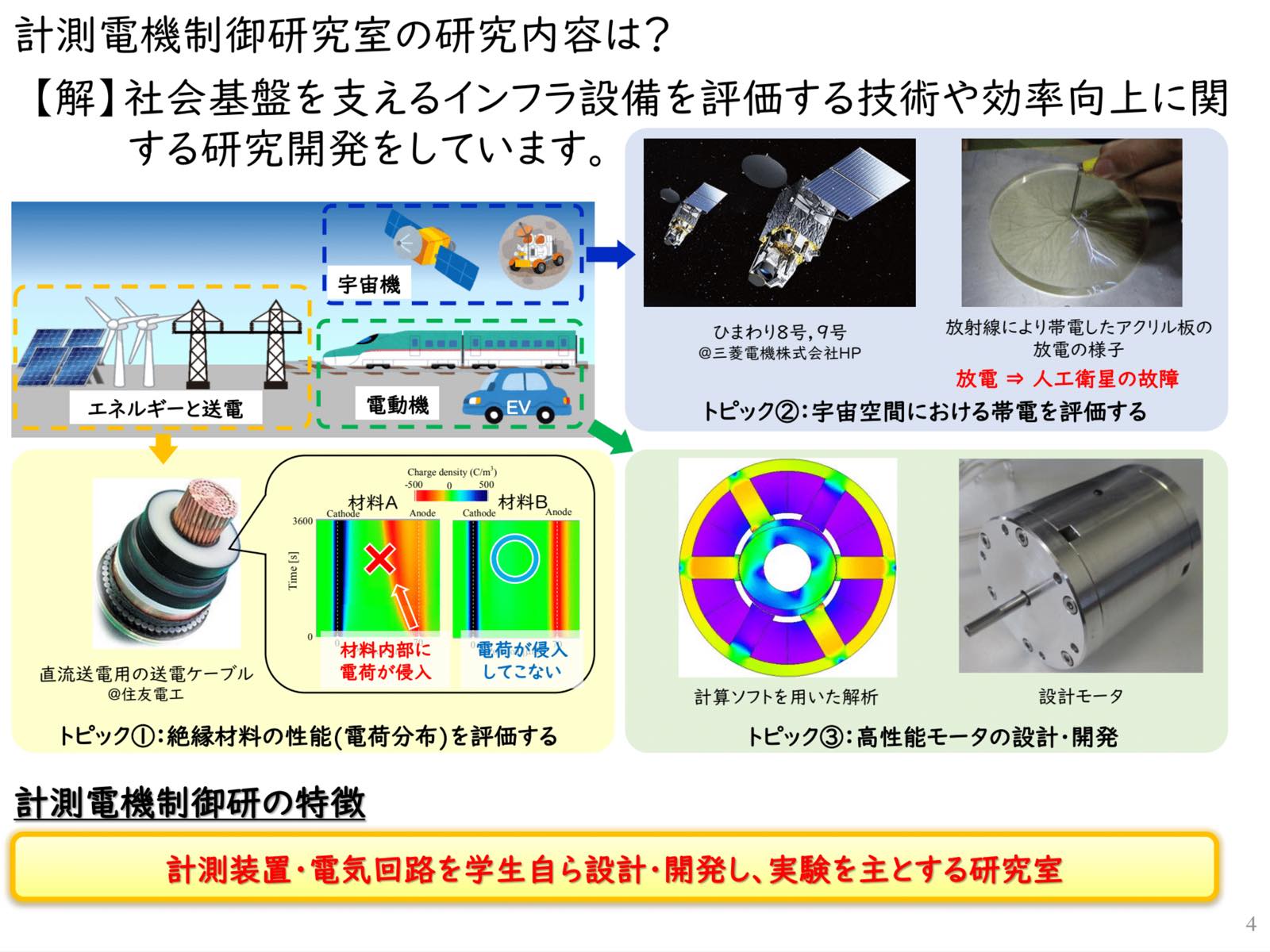

The Measurement and Electrical Control Laboratory, to which Professor MIYAKE belongs, evaluates a wide range of insulating materials. One example is power transmission cables. In order to realize a decarbonized society, electricity generation using renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, and hydropower is required. Due to their characteristics, renewable power plants are often built in suburban or offshore locations, making long-distance transmission to urban consumption centers necessary.

Conventional power transmission is generally based on alternating current (AC), but AC transmission suffers losses due to resistance in the transmission lines, resulting in significant energy loss over long distances. In addition, solar and wind power generate electricity in direct current (DC), making DC transmission more efficient.

The laboratory develops technologies to evaluate “electrical insulation properties,” which refer to a material’s ability to block electric current. By providing manufacturers with evaluation and analysis results, the laboratory contributes to the development of cables capable of safely carrying high-voltage direct current, which are already in practical use.

“We use ultrasonic waves and light with wavelengths shorter than ultraviolet rays for evaluation. Although insulators themselves do not conduct electricity, on a molecular level, electric charges gradually move and accumulate, which can eventually lead to breakdown. Cables for high-voltage DC transmission require exceptionally high insulation performance,” explains Professor MIYAKE.

Professor MIYAKE, who promotes research in collaboration with overseas institutions and is involved in national space policy, was asked what he feels is currently lacking in Japan.

“Perhaps tolerance. Our society is flooded with information, and I am concerned that people are losing their sense of flexibility and leeway. When comparing Japan with other countries, budget scales are inevitably different, but in the United States in particular, development often proceeds with the idea that ‘it’s okay if it breaks,’ and large-scale production is pursued. This naturally leads to better cost performance. I believe we should be more tolerant and freer in many respects,” says Professor MIYAKE.

During the interview, students in the laboratory could be seen analyzing data and preparing experiments. What does Professor MIYAKE expect of students and younger generations?

“Humanity has advanced technological innovation by seeking new frontiers. The deep sea and outer space are the next frontiers. We are pursuing research to measure charging in space itself, aiming to achieve the next wave of technological innovation. I hope students will grow into professionals who can contribute to society and help strengthen Japan’s technological capabilities,” he concludes.

Electric charge quietly accumulates on the surface of spacecraft, unnoticed by anyone. At times, it can determine the fate of space exploration itself. Professor MIYAKE does not overlook these subtle signs, capturing them as numerical data and transforming them into reliable technology. The knowledge and achievements generated in his laboratory will one day run through the silence of space like an electric current, becoming a light that opens up the next frontier.

Professor, Department of Mechanical Systems Engineering, Faculty of Science and Engineering, and Graduate School of Integrative Science and Engineering, Tokyo City University. Director, Research Center for Electronic Properties Measurement Technology, Advanced Research Laboratories, Tokyo City University. He received his Ph.D. in Engineering in 2005 from the Doctoral Program in Mechanical Systems Engineering, Graduate School of Engineering, Musashi Institute of Technology (currently Tokyo City University). After working at the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), he joined Tokyo City University, where he currently serves in his present position.